By Michael Streissguth, Rolling Stone | Eyewitnesses to the Man in Black’s legendary 1968 concerts at the California prison recall Cash’s shining moment. Decades after Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison album was recorded, it remains as mythical as ever. The concert and its star bore into the international imagination and for various reasons never left it. Dressed in his trademark black on January 13th, 1968, he paradoxically celebrated prison and outlaw life while creating a damning portrait of the prison experience that pricked the era’s concern for society’s outcasts. It was also the first live recording of a prison performance, and it crystalized Cash’s dark image. And then it thrust into the public spotlight chiseled inmate Glen Sherley, who embodied Cash’s belief that compassion for prisoners could lead to redemption for us all.

The stories around the Folsom album spiraled up like a dust devil, taking with it fevered speculation about Cash’s run-ins with the law and other half-truths and shady legends. Hollywood’s 2005 Walk the Line biopic portrayed the concert as something it was not, although it did get one thing right: On a very basic level, Folsom marked a personal and professional renaissance for Cash.

To bring it all down to earth, Rolling Stone has combined never-before-published interviews with three witnesses to the Folsom Prison shows: Marshall Grant, an original member of Cash’s Tennessee Two who played bass and held together his boss’s manic touring troupe from 1954 to 1980; drummer W.S. “Fluke” Holland, formerly with rockabilly legend Carl Perkins, who joined Cash in 1960 and remained with him until Cash’s last tour in the 1990s; and Jim Marshall, the king of rock & roll photographers who famously shot virtually every pop music star during his lifetime but counted himself most lucky to be with his camera at Folsom Prison. Marshall and Grant died in 2010 and 2011, respectively, while Holland lives today in Jackson, Tennessee, and fronts a band that honors the country music legend’s memory.

The three men re-trace Cash’s steps into California’s Folsom Prison on a chilly, gray day and resurrect his and June Carter’s unbridled performances for the men who seemed to count Cash as one of their own. Grant and Holland harken back to the power of Cash’s performance of Glen Sherley’s song “Greystone Chapel” and then its tragic aftermath. And who knew the Man in Black’s entourage carried through the prison gates both a concealed weapon and pellets of hash until Grant and Marshall revealed it for the first time in these interviews?

More surprising, perhaps, is that the Folsom concerts (Cash did two that day) was more than an act of compassion for the inmates, but also a ploy to coax from Cash another album when his drug use had stymied his record production. What further secrets does the Folsom story hold? The years to come may tell.

The Road to Folsom

Marshall Grant: This was a way to get something out of him to release, because we couldn’t get him in the studio. And when we got him in the studio, he’d come completely unprepared. He came in and would start writing songs. You can’t do that because every part of our career proves, especially with us and with him, you had to get the songs, work it up, have it ready to go. Well, we couldn’t get him to do that. So it came up through conversation, “Let’s do an album at Folsom Prison.”

Fluke Holland: I mean we’re going to Folsom, and we’re doing a show there to entertain the prisoners because they can’t get out to be entertained. It was like we just were doing a nice gesture. And I remember saying, as far as making money, this show, if you’re going to tape it and sell it, it won’t sell enough to pay for tape. I remember saying that two or three times. In fact, I remember saying it to Bob Johnston, who produced the thing. And it turned out to be one of the biggest things at that time that Johnny Cash ever did.

Jim Marshall: I don’t think any of us knew how important it would be. I photographed the last Beatles concert in 1966. It was 10,000 seats short of sold out because no one knew it would be the last concert the Beatles ever did. But I was fortunate to be at both those places. I think Folsom gained in importance over the years because of the rawness of it and the energy. And it’s amazing the energy on that record. But I didn’t know at the time how important it would be.

MG: John had a real feeling for the down and out, for the prisoners. For anybody like that. He came from very humble beginnings in Arkansas. So even though he acquired a lot of things in life, he still felt for these people and he made it very obvious, too. He was so real with it. And that’s what brought him to prisons. And a lot of them turned their lives around because of our willingness to go entertain them that told them that we cared.

JM: I think John believed he was just making the public more aware of the conditions in the prisons. As a spokesman when he did the show, I don’t think he saw himself as that. I think he saw himself as an entertainer who could make a difference in their lives even for an hour.

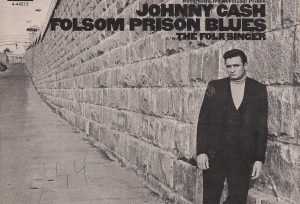

MG: When we got to Folsom, it was so quiet and so desolate and you could only see a few prisoners around. Jim Marshall took pictures of John and June on the bus and of them getting off of the bus and we were all in there and it was a rolling jail cell. And so even from the time we left the little motel, which was two or three miles away, it was a very somber atmosphere for everybody. It was hard to explain. There was just no joy here.

The atmosphere in there is unlike any place you’ve ever been in your entire life. Whatever you saw outside is exactly the opposite of what you see in here. And everybody is controlled. Everybody is watched, including us. We were prisoners in these prisons. So that sort of made it uncomfortable. It didn’t mean that the prison guards weren’t nice about it, but they had rules and regulations that we had to abide by, and we weren’t going to break those rules.

JM: We just got off the bus. And these granite walls are like 18 feet high, and we got off the bus inside the second set of giant gates, and they clanked shut and John goes, “Jim, that sound has a feeling of permanence about it.” You know, I’m thinking, “Oh, goddamn.” Because only a year before, I was arrested for shooting somebody. I could have been in there. In fact, I was on probation when we went to Folsom.

MG: I carried this gun into Folsom, which was a real gun that we used as part of a gag on stage. You pulled the trigger and it would smoke. It was loud, and it was so funny that people just absolutely loved it on the show. Well, I carried it in my bass case. I didn’t think anything about it. But when I went to get my bass out and I saw the gun in the bass case, I said, “Oh my God, I’m in Folsom Prison with a gun! I probably will spend the rest of my life here.” So I very quietly went over to a security guard who was stationed on the stage and I explained to him exactly what it was all about, and I said, “I don’t want no problems.” He said, “Well, don’t worry about it. I will get a couple of security guards to go with me and we’ll take it and explain it to the warden and we’ll lock it up until you get ready to go.”

JM: I had a couple of little balls of hash in my camera bag that I’d forgot about, and they didn’t find it, obviously. But can you imagine going into a prison with some drugs on you? God! I had Levi’s jeans on, and they said, “You can’t come in with Levi’s because [you’ll blend in with] the prisoners in their blue jeans.” They had to get a pair of khakis for me.

The Show

> > > > > > > > >

This article was originally published on May 7, 2018, by Rolling Stone. Read the whole article here: https://getpocket.com/explore/item/johnny-cash-s-at-folsom-prison-at-50-an-oral-history